Something’s not right, you think to yourself.

It’s Saturday night. Your body and mind are soft and booming with the last vapor trails of a speed cap you took in the morning.

The capsules are time-release; over the course of twelve hours your skin has been suffused with a cocktail of amphetamine salts, each metabolized at a different rate. This is how you get through work, and from work, here.

You let him drive you back to his place, where the TV’s surround sound blathers and blares through the living room, eating away at your concentration, eating away at whatever the hell it is he’s been going on and on about, the way he always does. Maybe that’s for the best. The 11 o’clock news just started but it’s all a white roar.

You’ve got what you came for. You need to start the walk home.

You won the lottery tonight. After a dry week he finally came through and hooked you up with a sack of vibrant, pungent buds. You rub the smolder of the shared joint out with spit and finger.

He always lets you keep the roaches; he wouldn’t deign to touch it now. Too small.

All night long the dark, salted with yellow and blue streetlights, has pressed against his windows like a poultice, drawing you out. Late spring in Lorain, it says.

There are houses along railroad tracks, running like a rough scar.

The Black River bifurcates the city, East, West, crossed by two bridges: the Charles Berry bascule and the Lofton Henderson 21st Street Bridge. As far as you’re concerned, both bridges have their charm when it comes to walking home. Charles Berry is the closest of the two, just four blocks away from his house, and it’s also the smaller bridge. Crossing it takes you right into the thick of downtown Lorain.

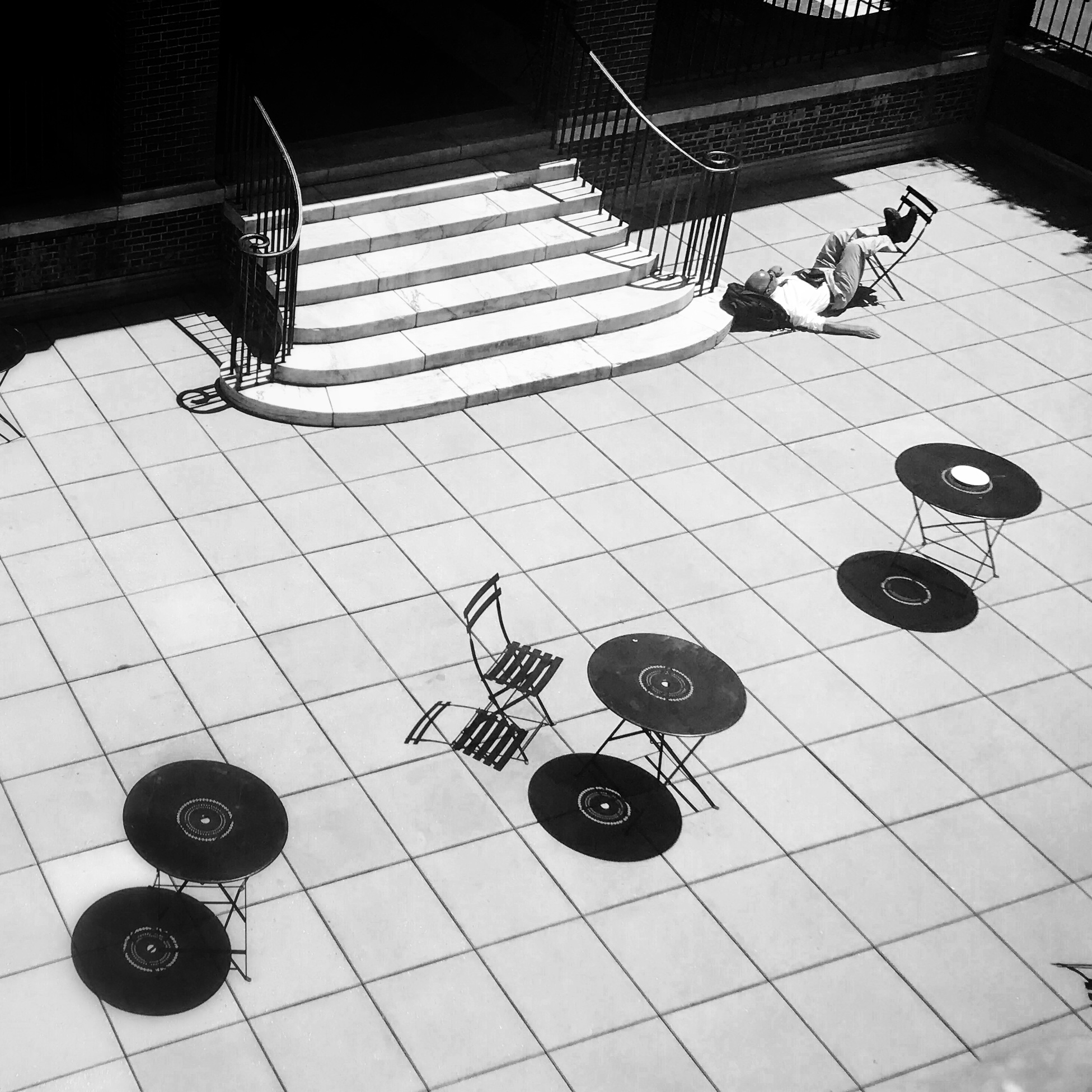

Broadway begins with a left off the bridge. The architecture here always whispers to you of life in a previous century; every block of downtown is flanked by a stone facade, eagles and ornate corners carved to watch as you pass on the wide sidewalk below. The bars seem empty, dark, though it’s just after midnight and Saturday as well. This part of Broadway is easily the best-lit section of the city, and the streetlights, stylized faux-iron lamps, hold the purple dark off the pavement, engineering sharp, skittering shadows that roll across the sidewalk and catch you unaware as you stumble to the beat in your headphones.

This walking, you think, one foot gliding before the other: this means something to me. My dreams are infused with its images. Stark, blind buildings flow over your mouth as you sleep and choke your breath with their emptiness; sidewalks dry and blue, tree-lawns cacophonous with abruptly dropped dolls and upturned tricycles; the sense of the whole city unreeling through your body, and the sense that you could punch a hole in it with your finger, that it would pop and the hole would shrivel and blacken brightly like botched film. This is where I live, you think.

Stumbling forward as the spectacle bursts.

Streetlights hollow out the last of the gaunt churches on Reid Avenue. Dark ripples in stone, they’re embarrassed at their gothic bawdiness; all around them, squat houses squint with windows, shrink.

Because in your dreams too you’re walking and in your dreams it’s all de Chirico. Some feeling, bit of memory, you think. As if pavement and box buildings leering are a way to remember rust. Like walking raw the bottom of the ocean, just barely remembering that you need air.

So it’s something like death?

Hmmm, why would you say that?

Well, that’s what would happen. If you walked on the bottom of the ocean long enough. And remember what you said about not breathing?

Covering you over, coughing, slipping from the channels.

I’m nothing if not a religious man.

Like a monk, I’d say.

You make a left from Reid onto 12th Street. Between 11th and 12th railroad tracks stretch beneath streetlights like the ribs of a long snake, long dead. There’s some sort of small industrial building at this corner, and on previous walks the desolate aura around the place intrigued you. You slip the headphones off your ears. This is a dark street, one you haven’t explored before, and you want to hear it. This isn’t a neighborhood one strolls through casually at night; many of the low, peeling houses have the starved wolfish look of crack houses, dark windows peering blindly back as you pass. Eyes that no longer admit light.

This street runs parallel with the tracks. Between sparse residences patches of trees and undergrowth strain to reclaim. As you walk the trees at some intervals achieve complete saturation; both sides of the street swoon with the hushed motion of leaves. These patches you walk slightly faster through. With so few street lights here, passing into one of these wooded intervals is like falling down a well; a well alive with cricket sonatas and unseen sinister dance.

Falling down and crawling out.

When you hear the toilet flush you know Dad’s done. It’s a welcome sound. You’ve been standing outside the bathroom door for what seems hours, listening to the tide of hush that is your family, asleep. For some reason you think of Mr. Murphy as you wait. He owned the house before your family did, and his name has become tangled in your mind somehow. You heard he died. That’s how your family could buy this big house on 12th Street.

Everything you know about death comes from Saturday afternoon horror movies.

The pop of the door cuts your thoughts. Dad stands for a minute, fifteen feet tall in the doorway, harsh bathroom light throwing his thick arms into relief. Then he flicks the switch, and mumbles something unintelligible in a voice so deep you hear it in the old house’s beams.

You have no idea how long you’ve been staring at it.

White misty light in the shape of a man gliding up the stairs.

White misty light in the shape of a man gliding up the stairs.

White misty light in the shape of a man gliding up the stairs.

Many of the streets next to railroad tracks in Lorain host these predictable industrial buildings. Some are small machining shops; others build furnaces. Many are closed and deserted. One of these is on Long Avenue, and it’s circled by a chain link fence. The fence has been reinforced with green plastic, blocking for the most part any view of the property. He owned the house before your family did. Every house across the street from it is empty. This is a good neighborhood, Mom says. What hasn’t been boarded up on this street has been abandoned; smashed, jagged, scattered on the lawn.

It’s on your way down Long Avenue that it hits you. It’s late Spring, early Summer. It’s a warm night. It’s not horribly late, just a bit after one in the morning, on a Saturday night. And you haven’t seen one other human being while you’ve been on this walk.