When you hear the noise in the baby monitor, you think it’s just regular static, erupting from the speaker like steel wool on concrete, no perceivable origin. Sometimes, you pick up semis on the freeway down the hill, voices come through on cousin channels to the one your monitor uses. You never know what it is they’re speaking of, just snippets of drawling male voices.

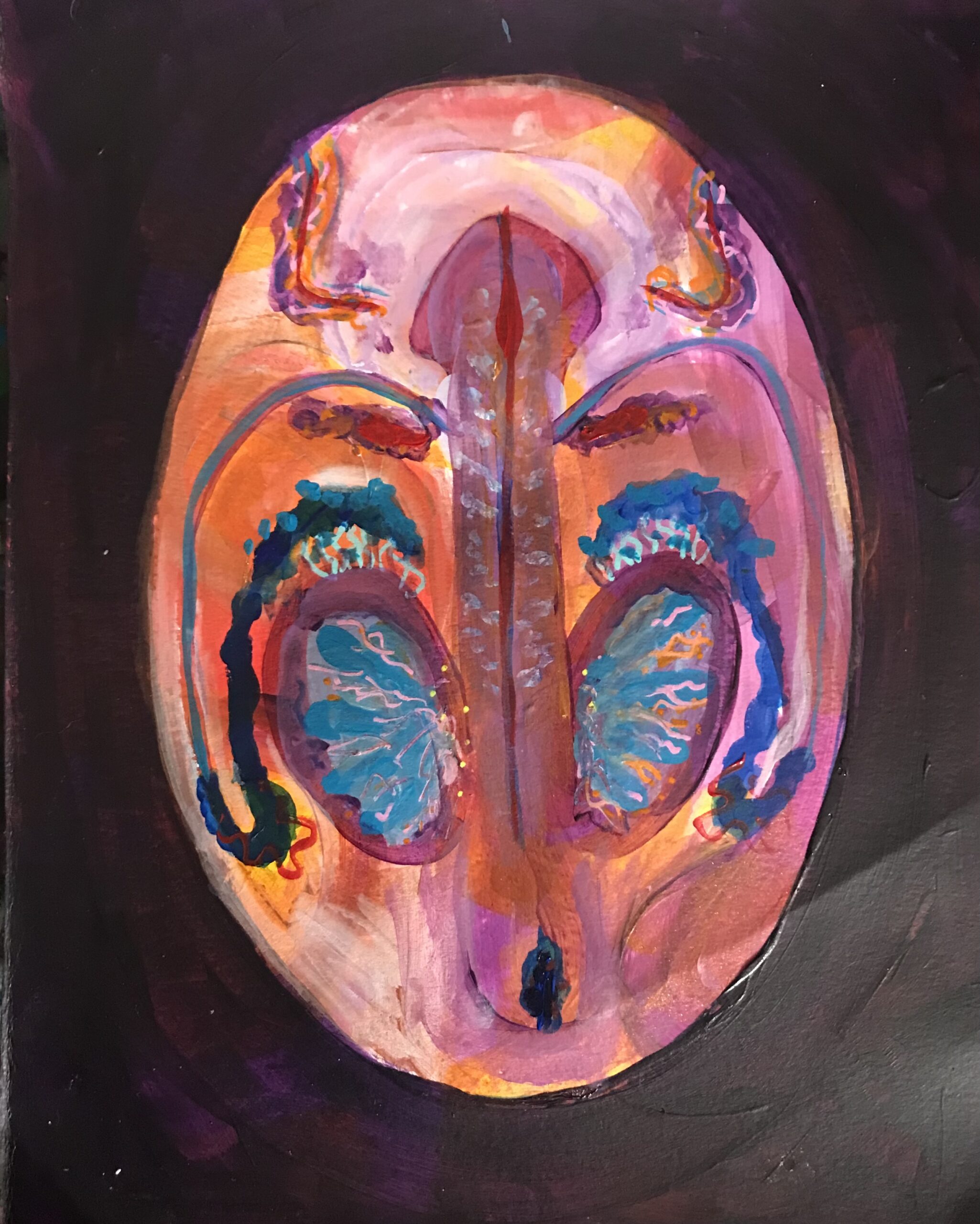

But then once, a distinct voice. You are in the shed your husband converted into a studio when he convinced you that living thirty-five minutes from the nearest town would be a quiet, restful, and safe place to raise a family. You’ll have space to paint, he repeated, as though you weren’t already painting in the evenings on the little balcony porch you decorated with potted azaleas and teacup roses. Or at the end of the long dinner table which generally gathered a month’s worth of junk-mail circulars, scraps from paid bills, jackets shed and tossed. Or in the park. Or at a table outside the corner cafe where you often showed up before the barista and waited with what you thought was pleasant patience while they grumpily opened and begrudgingly thanked you for the five-dollar tips.

You don’t begrudge them. You remember those kinds of jobs keeping you afloat during art school, one of which was where you met your husband, a man older enough that his aloofness endeared him to you. You know he was telling himself a story about saving you from impoverished ignominy – “the artist’s fate,” he would joke-not-joke – just as you tell yourself you are saving him from a life where dollar signs stamp out beauty.

Still, even with his impressive salary, the apartment you could afford was a shoebox, a step up from the matchbox you had been sharing with three other women.

And when you became pregnant, the city seemed abruptly cold, distant, dangerous, and filthy. He found the house in the country, a gem over 150 years old but updated with modern conveniences. Land and forests surrounding you. Peace and quiet. You filled the space with Americana and rusted-over antique appliances. You covered the counters with locally-made ceramic canisters and jars. You sat on the porch steps and listened to the house tick and creak.

So when you’re standing at your easel and the monitor crackles and a woman’s voice comes over the receiver, your brush pauses over the canvas. It is distinctly female. Distinctly in the room with the baby.

You race for the backdoor and run through it, left open for safety’s sake. You take the stairs two at a time and slam into the baby’s room, making her howl against the deep sleep from which you have snatched her, and you have your paint brush clasped like a dagger in your fist, ready to gouge eyes. No one is there.

As a child, your father used to tell bedtime stories of the Lindbergh kidnapping. Your eyes drifted closed to images of a ladder leaning against a clapboard house, one of the rungs broken. Bags of money in a dusty shed. An infant’s decomposing body in the woods.

He was also obsessed with the Rosenbergs and populated your dreams with tales of espionage and treachery. Men in dark overcoats. Women clacking away at typewriters, ripping documents out with a flourish, putting them in khaki folders – dossiers – and sliding them under doors.

As a child, you thought the events happened concurrently.

Even still, they get mixed up in your dreams. Babies in electric chairs. Sheds full of ladders. Climbing up and up and up and up and up, falling down down down.

When you tell your husband you’ve been hearing voices in the monitor, his face makes an expression you’ve never seen before and distinctly dislike.

You keep hearing the voices. You sit on the basement steps because it is immediately below the baby’s room and the reception is best there. In the dark. The quiet.

A woman. Sometimes a man. You cannot hear what they are saying, just the tenor of their voices. Warm and nurturing. They make soothing sounds as she tumbles and rolls in her infantile sleep. When you click the button that turns on the camera, the voices stop too. As if they know. They don’t return. You stop trying to see. You only permit yourself to listen.

Your husband finds you asleep on the basement stairs. He suggests your mother might like to come for a visit, meet the baby, stay for a while. To help.

You wait until he is asleep before making a nest on the basement steps, setting an alarm half an hour before his. You place the baby monitor where it will blink right in front of your eyes and wake you should they speak.

He finds you. Not the first time you do this. But eventually. He takes you around the house, holding your hand, unlocking and relocking all the windows.

You find a ladder in the garage, left by the previous owners. After you put the baby down for her nap, you tiptoe out the backdoor, the monitor attached to your head at ear level, a little creation made with some elastics and an old sweatband of your husband’s.

Once the baby is settled, you climb the ladder and perch on a rung below the lip of the windowsill. You wait. You listen.

The voices come through thready and whisper-light. You scramble up to the top of the ladder. One of its aluminum feet sinks into loose soil from the calla lillies your husband was planting for your anniversary. As the ladder tips away from the house, you hear their words, tight to your ear.

Did you hear that?

Hear what?

Outside the window.

There’s nothing outside the window. Shhh, now, don’t wake the baby.

Such an angel.

A pity about the mother.